Periodization has its roots all the way back to the days of ancient Greece and it’s still at the core of most athletes training plans. As our knowledge and methodologies become more advanced, so has our concept of periodization. However, not all types of periodization are the same, and the “old school” styles of periodization do not make sense for most athletes. In this series, we will compare the two major styles of periodization, traditional and block in order to help you determine which model makes the most sense for your training.

Roots of Traditional Periodization

In ancient Greece, ahletes training for the Olympics would complete 11 months of rigorous training in order to be at their peak for the one main event—but the term “periodization” came to prominence in the 1960s in training Olympic athletes.

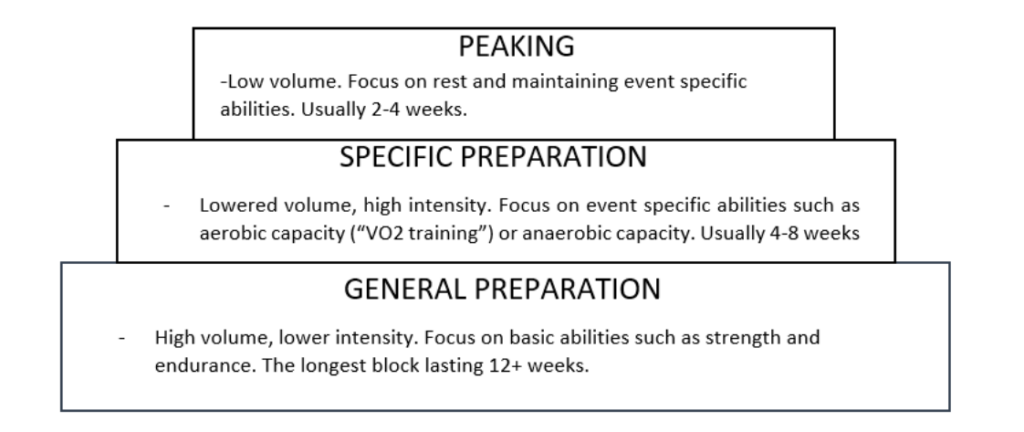

These early days of periodization reflect what we now know as traditional periodization, whereby a large General Preparation phase (endurance athletes know this as base training) is followed by race-specific training close to the main event. The primary idea behind traditional sequenced periodization is to prepare an athlete for a major peak during their training cycle. In this model, athletes will complete large volumes of less specific training before an event specific block, followed by a taper.

Limitations of the Traditional Sequenced Model

Traditional sequenced periodization is remarkably effective if you only have a handful of events throughout the year. However, this model does not make sense for most athletes in the modern era. There are many more events for athletes to participate in than in the past, and the number of events littered throughout the year do not lend themselves to a simple traditional model. Many athletes have multiple goals scattered on their calendar. Here are the main limitations of the traditional model:

- Maintenance of skills: The traditional sequenced model of periodization only has one main focus during each training phase. A long racing season spent focusing solely on event-specific abilities will cause a decline in base fitness and eventually lead to burnout. Conversely, a long winter focused exclusively on low-intensity training does not lend itself well to improvements, particularly for those with limited training time.

- Lack of Variation: A key to an effective training program is variation. In order to improve, one must introduce new types of training. The body adapts quickly to a new stimulus and if training is not varied frequently, this can cause a plateau whereby the body is no longer challenged by the same workouts. The fitter you get, the more you must introduce new and challenging stimuli to your training. Traditional periodization may not offer enough variation to more advanced athletes who are seeking to improve.

- Boredom: A long training cycle with one main focus can cause boredom. If you spend the entire off-season doing nothing but long-slow distance or tempo workouts, there’s a chance you’ll get bored. Completing the same mid-week high intensity workouts during the entire racing season can also lead to “staleness.”

- Not realistic: For most of us the off-season occurs during winter, which means short days and bad weather. It is not realistic for an athlete with a job and/or family to do large amounts of volume throughout the winter. Traditional sequenced periodization will be much less effective if there is not a large amount of volume during the General Prep phase.

Block Periodization: A New Type of Periodization

During the 80s and 90s, coaches began to realize that classical models of periodization had limitations for many modern-day sports. Commercialization of sports increased the number of important events. Coaches needed to find a way to get their athletes in peak form multiple times during the year and hold their peak form for longer without going over the edge.

These identified limitations led to the development of block periodization. Block periodization has gained traction among many coaches and has been proven as a sound means of an effective program.

Block periodization features smaller, more focused training cycles as opposed to the long training mesocycles found in traditional periodization. This allows for greater customization depending on the athlete’s calendar and the ability to program for multiple peaks. The smaller training blocks keep things fun and engaging for the athlete and prevent burnout.

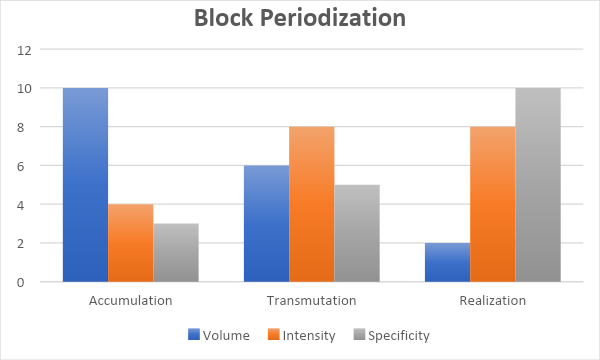

There are 3 main types of phases within each block in the block periodization model. The first is the accumulation phase. This has a similar focus to a base training mesocycle found in the traditional model but it is shorter, usually around 2-6 weeks. The primary focus is on accumulating large amounts of volume at a lower intensity to lay the foundation for the future phases.

The second phase is the transmutation phase. In this phase, focused high intensity workouts take precedence. In the block model, these primarily focus on developing one energy system. It is in this phase that the athlete can improve their limiters or do event-specific training leading up to an event. This block is mentally and physically taxing so it only lasts 2-4 weeks.

The last phase is the realization phase. This is typically either a taper before a race or a rest week during a training period. Usually lasting 8-14 days, this phase allows the athlete to recover and prepare for the upcoming event. Race-specific training is interspersed throughout this phase but the primary focus is recovery.

Each of these 3 phases will comprise a single block. A block can be used to prepare for a specific event, or it can be used to train a specific ability during a training cycle. The blocks last anywhere form 5-10 weeks. This is in stark contrast to a 20+ week training cycle found in the traditional model. The figure below shows the primary focuses of each phase.

There are a few core concepts that make block periodization unique:

- Training residuals: Each skill has a residual. In other words, after a specific is ability is trained, there is a set amount of time before this ability is lost when it is not trained. For example, if I do an accumulation phase focused on aerobic base and then begin a transmutation phase focusing on high intensity with low volume, it will be 25-35 days before my aerobic ability deteriorates and becomes a limiter to my performance.

- Variation: Block periodization capitalizes on the idea of training variation. By varying the stimulus in each phase, the body is kept “on its toes” and will continue to respond to the new stimuli, preventing a plateau.

- System overload: Each training phase is highly focused on one primary skill. This allows the athlete to overload the body in a way that would be difficult with a traditional model. More advanced athletes require large amounts of overload to improve a specific skill. Block periodization allows an athlete to continually improve their focus areas. The shortened blocks in this model help to prevent overtraining of one ability or a plateau in fitness.

- Restitution: After a specific ability is trained, that system will be given sufficient time to restore itself while a different ability is trained in the next phase. This allows the athlete to continually improve on certain skills while preventing overtraining.

Block periodization offers many benefits to more athletes with busy seasons and multiple targets during the season. It is an ideal way for long-time athletes to improve their fitness with targeted overload. However, it’s not best for everyone. Like the traditional model, it also has its limitations:

- Complex: The block model has many nuances and these must be understood for the program to be effective. If the training blocks are changed too often this can lead to “confusion” in the body, whereby a specific system does not have sufficient time to be improved.

Additionally, it can be difficult to perfectly time blocks to elicit optimal performance. For these reasons, block periodization should only be implemented by coaches or those with a great understanding of this training method. It also takes more time to program with this complex model; a busy self-coached athlete may not have the time necessary to develop an optimal plan and may want to seek out guidance from a coach.

- Not for Beginners: The block periodization model is more designed for experienced athletes. Beginners will likely benefit more from focusing on consistency in their training rather than a complex system of training. Block periodization is something that can be incorporated after an athlete has sufficiently developed their basic abilities.

That’s a basic overview of the block periodization model. In the part 2 of this series, we will look at how to program a season using the block model.

References

Haff, G.G., & Haff, E.E. (2012). Training Integration and Periodization. In Jay Hoffman (Eds.). NSCA’s Guide to Program Design (pp. 209-254). Location: Human Kinetics.

Issurin, V.B. (2007). A Modern Approach to High-Performance Training: the Block Composition Concept. In: Blumenstein, B. et al. Psychology of Sport Training. Oxford: Meyer & Meyer Sport. p. 216-34.

Issurin, V.B. (2010, March 1). New Horizons for the Methodology and Physiology of Training Periodization. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20199119/