As coaches, we have a plethora of tools in our toolbox. As such, we use these tools to help guide athletes into a certain “training zone” to ideally elicit a specific physiological response.

A common misnomer I often see is assuming a certain power number equals a certain physiological response, particularly when it comes to VO2 max prescription. In reality, VO2 max sessions are about maximizing time spent near VO2 max (the physiology), not maximizing minutes in a specific power zone (the output).

The Real Target: Time Near VO₂max

In a lab, the target is time at ~90–100% of VO₂max (depending on the protocol). In the field, we don’t have VO2 ventilation data, so we rely on proxies:

- Breathing: unmistakably heavy ventilation (“can’t talk”), not just leg burn.

- Heart rate: ramps across early reps then sits high late in the set (not necessarily at max HR, but clearly near the top of the athlete’s range for repeatable work).

- RPE: very hard, (9-10/10) but controlled—athlete can repeat with similar quality.

- Power stability: minimal fade across reps (fade often signals you went too anaerobic early).

When coaches miss the target, it’s usually because the athlete spends too much of the interval block getting up to VO₂ territory and not enough time staying there.

VO₂ Kinetics: The “time-to-get-there” Problem

VO2 kinetics describes how quickly oxygen uptake rises when intensity increases.

When starting an effort/interval, it might take 60-90 seconds before even reaching the desired percentage of VO2 max. This varies across individuals:

- Fast kinetics: the athlete reaches high VO2 quickly → more time near VO₂max within each rep and across the set.

- Slow kinetics: VO2 rises slowly → a lot of “hard time” happens below the real target, unless the set structure forces VO2 to stay elevated.

This is why some athletes feel that Tabata-style workouts like 30/30s are “hard but manageable,” while 4–5-minute reps feel like a completely different level of respiratory stress. For them, the short on/off format may never keep VO₂ elevated long enough—unless it’s designed correctly.

Key coaching takeaway:

Your job isn’t just picking an intensity. It’s picking a structure that matches the athlete’s kinetics.

VO2 Ceiling vs. VO2 Kinetics: Which to Prescribe?

Most athletes need both, but they usually lean toward one.

1. “Ceiling-limited” athletes

These athletes typically need higher VO2 max capacity work. Common signs:

- Strong steady-state / threshold work but lacks punch above it

- 4–6 minute reps are sustainable but not high power

- Races feel okay until repeated surges expose a lack of top-end aerobic power

Athletes that fall into this category often respond well to classic 3–5-minute intervals at high aerobic power (115%+ FTP), with sufficient recovery to maintain quality.

2. “Kinetics-limited” athletes

Kinetics-limited athletes need a faster ramp into Vo2 max and can stay near the ceiling. Signs of these kinds of athletes include:

- High anaerobic contribution early, then fades.

- Short intervals feel “fine” but don’t create a big respiratory load.

- HR takes a long time to climb; the athlete spends half the workout “not quite there.”

These athletes often do best with structures that keep VO₂ elevated: shorter recoveries, longer sets, and/or a primer.

The Biggest Mistake: Chasing Watts Instead of Response

If your athlete treats VO2 max work like a max-effort contest, the workout often becomes:

- too anaerobic early,

- too much fade, i.e. peripheral stress limits systemic stress,

- too much recovery needed after, and

- paradoxically, less time near VO₂max.

A better model would:

- start controlled,

- let HR/ventilation rise, and

- Allow the athlete to finish strong without blowing up.

A Coach’s Field Checklist for VO2 Max Targets

Green lights (likely good VO2 max stimulus):

- HR ramps over the first 2–4 reps and stays high across later reps within a set.

- Athlete reports dominant breathing stress (not just legs).

- Power is consistent across reps/sets (small fade is okay; collapse is not).

- Recovery between reps doesn’t fully reset (VO₂ stays elevated).

Red flags (often not a VO₂-focused session):

- HR never climbs meaningfully across reps.

- Athlete says “legs are screaming” but breathing never felt maximal.

- Huge first rep, then dramatic fade.

- Recoveries are too easy/long (each rep starts from scratch).

- Athlete needs days to recover (you likely turned it into an anaerobic smashfest).

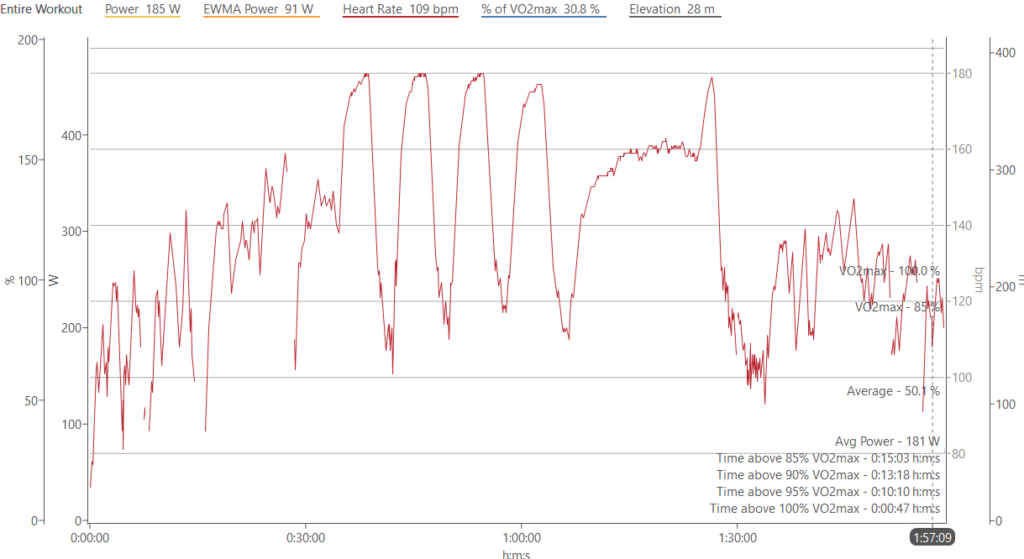

Assessing Time at VO2 Max

The main stimulus we are looking for in a VO2 max interval set is maximizing time at or above 90% VO2 max.

Certain power prescriptions can get the athlete there, but metrics like heart rate, ventilatory rate and RPE are needed to verify. Some things to look for include:

- Heart rate plateau (or starting to plateau),

- High ventilatory rate (on the verge of hyperventilation, feedback from athletes needed)

- High RPE (10/10 but without a huge power fade over subsequent efforts).

Coaching Tip→ Estimating time at 90% VO2 max or above can be kind of tricky, but such as tools such as the Relative VO2 Max Chart in WKO5 to get a more accurate estimate.

Workout Menu: Choosing a Structure That Fits the Athlete

Below are reliable go-to sessions, with coaching notes on who they’re for and how to progress them.

1. Classic VO₂ repeats (best for raising the ceiling)

Option 1: 4 × 4 min (or 3 × 5 min)

- Recovery: 1:1 (4 min easy)

- Intensity: hard but repeatable; last rep is a fight, not a failure

- Best for: ceiling-limited athletes

- Progression: 4×4 → 5×4 → 6×4 OR 4×5 → 5×5.

Option 2: 6 × 3 min

- Recovery: 2–3 min easy

- Best for: athletes who struggle to hold quality for 4–5 minutes and have an early VO2 block.

- Progression: add reps (6→7→8) before raising intensity.

2. Micro-intervals (can be great—if VO2 stays elevated)

Option 1: 3 sets of 10 min of 30/15s (30 hard / 15 easy)

- Recovery: 5 min easy between sets

- Best for kinetics-limited athletes, racers who need repeatability, and time-efficient sessions.

- Coaching cue: keep “easy” truly easy but short; don’t let breathing fully reset.

- Progression: 2×10 min → 3×10 min → 3×12 min.

Option 2: 2–3 sets of 8 min of 40/20s

- Similar benefits, sometimes more tolerable.

- Best for athletes who handles micro work well but needs more sustained strain.

- Progression: add a set, then extend set length.

Avoid this common micro-interval pitfall:

If the recoveries are too long/easy, the athlete never accumulates enough time near VO2 max. Micro work should feel like a continuous fight to breathe, not a series of sprints.

3. The primer (a simple hack for slow kinetics)

A primer is a controlled pre-load that raises VO₂ before the “real” intervals so the athlete reaches VO2 max territory sooner.

Primer example (before your main VO2 max set):

- 6–8 min at “very hard but controlled” (around upper threshold / low VO₂ feel)

- 2–3 min easy

- Start the interval block

- Best for athletes whose HR rises slowly and the early reps of VO2 max work don’t feel “aerobic-max.”

Don’t overuse: If every session needs a primer, the athlete may be too fatigued, or the main set structure may not be set up correctly.

Keep VO₂ training sustainable

Many coaches progress VO₂ by increasing intensity. A more sustainable approach might look more like this:

- Add repeatable work first (more reps or longer sets)

- Tighten recoveries second (only as needed to keep VO2 elevated)

- Increase intensity last (small bumps, only if quality remains high)

How often Should You Schedule Vo2 Max Sessions?

For most trained cyclists:

- 1×/week is enough to drive progress while keeping the rest of the week productive.

- 2×/week can work in a short block (2–4 weeks) if:

- the athlete is sleeping/eating well,

- the rest of training is dialed,

- and quality stays high (no repeated failures).

Quick Coach Cheat Sheet

Goal: maximize time near VO2 max, not just time in Zone 5.

Pick classic repeats when:

- The athlete is ceiling-limited

- You want the clearest respiratory signal

- You need simple progression

Pick micro-intervals when:

- The athlete is kinetics-limited

- You want density and repeatability

- You need race-like stochastic work

Add a primer when:

- Early reps don’t reach strong ventilation/HR

- Kinetics are clearly slow

- Micro-intervals feel “hard” but not “VO2 max hard”

If power is high but HR/ventilation isn’t:

- Shorten recoveries

- Lengthen the set

- Control the first few reps

- Consider a primer

The most effective VO2 max sessions consistently drive sustained time near the athlete’s VO₂ ceiling, which means choosing interval structures that match individual oxygen kinetics, verifying the response with simple field proxies (breathing, HR behavior, RPE, and power stability), and progressing density before intensity.

If you build sessions around the athlete’s physiology instead of the watts, you’ll get more aerobic adaptation with less unnecessary fatigue—and more repeatable quality across the entire training week.