Triathlon is an ultra-endurance event testing the boundaries of human tenacity. The overwhelming demands placed on the body across the three disciplines of swimming, cycling and running are often the main attraction to the sport.

Unfortunately, reported cases of sudden death in the triathlon have raised concerns about the safety of this event. Despite this, there remains a lack of information about the prevalence and causes of triathlon deaths.More importantly, there are unanswered questions as to if and how triathletes should undergo pre-participation heart screening.

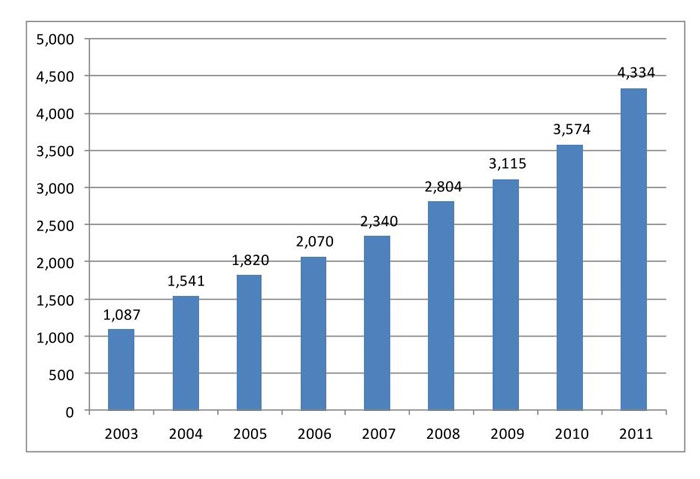

The popularity of the sport has increased tremendously since its origin in 1920s France where it was referred to as Les trois sports (the three sports). Triathlon events and participant numbers have more than doubled in recent times.

In 2011, in America alone, there were more than 500,000 athletes competing in more than 4,000 races, compared to 276,000 participants and 2,070 events in 2006 (1).

There is only one large study on sudden death during a triathlon. Researchers in the USA studied almost 1,000,000 triathletes competing in approximately 3,000 triathlon events between January 2006 through September 2008 (2).

They gathered data from two large American registries and obtained post mortem reports from medical examiners. Overall there were 14 deaths during this period which corresponds to 1.5 in 100,000 participants.

Most deaths occurred in males (80 percent) and middle-aged runners (median age 44 years). All of the deaths happened during the swimming stage of the race, apart from one cycling fatality, which occurred as a result of neck injuries following a fall.

Only nine of the 14 deaths had post-mortem data. Cardiovascular causes featured heavily as the cause of the death (80 percent); Six had mild left ventricular hypertrophy, including one with a clinical history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, and one had a congenital coronary arterial anomaly (2).

In addition, recently released data from USA Triathlon (USAT) has provided more information on risk factors. A panel was asked to review information about fatalities that occurred at USAT-sanctioned events between 2003 and 2011.

In those nine years, nearly 23,000 sanctioned events were held, involving more than three million participants.

The overall fatality rate for competing triathletes was approximately one per 76,000 participants. Among the 43 race-related athlete deaths, five were traumatic, caused by injuries sustained in cycling crashes; the remaining 38 deaths were non-traumatic.

Of the 38 non-traumatic fatalities, 30 occurred during the swim, three occurred during cycling, three occurred during the run, and two occurred after an athlete had completed the race.

Several important conclusions were made by USAT. Firstly, the fatality rate does not appear to be related to race factors such as length of the race, the type of swim venue, and the method of swim start (e.g., mass, wave or time trial).

Secondly, victims appear to have included athletes from a broad range of triathlon experience and fatalities were not confined to inexperienced triathletes. Among the major recommendations put forward by USAT to athletes was to “Visit your doctor for a physical examination with an emphasis on heart health before participating.”

There are several possible reasons why the swimming portion of the race is the most dangerous. The beginning of the swim race is the most chaotic part of the event with competitors bumping into each other as they jostle for positions.

Being knocked unconscious in deep water can be fatal, even for only seconds. In addition, diving into cold water is a recognized trigger for sudden death in a condition called long QT syndrome (LQTS).

This is an ion channel disorder characterised by a prolongation of the QT interval on a heart tracing (electrocardiogram). Death is often due to fatal arrhythmias mediated by adrenaline surges such as cold water immersion.

Finally, many deaths are thought to be secondary to a phenomenon called Swimming Induced Pulmonary Edema (SIPE). SIPE is well recognized in swimmers and divers and is caused by raised pressures in the lungs as a direct result of body reflexes secondary to cold water.

The exact mechanism is not fully understood but is thought to be a combination of blood vessel constriction and pooling of blood from the peripheries to the heart and lungs.

Although there is a paucity of data with regards to triathlon, there is ample information concerning marathons. The incidence of sudden death in marathons varies widely from 0.54 to 2.1 per 100,000 participants between reports (3).

Depending on some estimates, therefore, triathlons may be considered more of a risk than marathons. In addition, the major cause of death in marathon runners is coronary artery disease, whereas this did not feature in any of the triathlon deaths mentioned above.

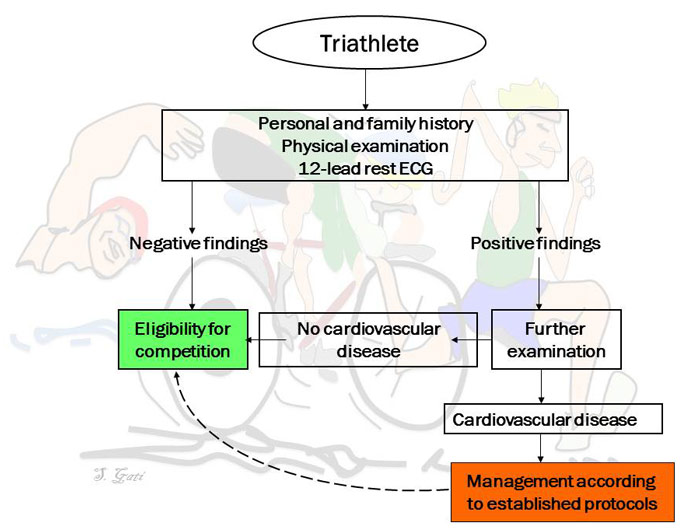

The ultimate question is whether triathletes should undergo pre-participation cardiac screening. Screening is a novel concept in triathlons and marathons, which attract enormous numbers of participants of varying ages and experience.

However, in professional competitive sports screening is now commonplace and even mandatory in some countries. It is endorsed by several professional sporting bodies such as FIFA and the International Olympic Committee (IOC).

Most of the documented causes of deaths in triathletes are treatable and can be easily picked up by simple tests such as a heart tracing (electrocardiogram or ECG) and a heart ultrasound scan (echocardiogram).

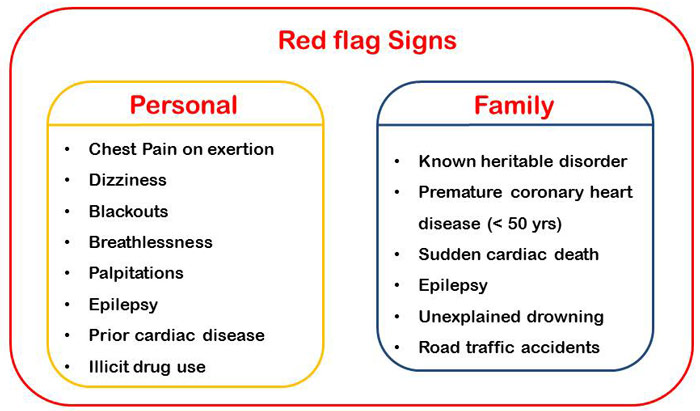

The yield from such testing can be increased in the presence of prodromal symptoms or a positive family history which can be gathered from a simple health questionnaire.

A widely accepted screening model based on the European society of cardiology (ESC) consists of a health questionnaire, physical examination and an ECG. Should these be abnormal, an ultrasound scan of the heart known as an echocardiogram is performed.

These simple measures would diagnose the vast majority of heart disorders(4). Additional tests such as cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET), cardiac MRI and genetic tests are warranted when further information is required to make a diagnosis or for the purpose of research.

The Centre for Sports Cardiology and Inherited Cardiac Diseases at St George’s Hospital, London, and the affiliated charitable organization, Cardiac risk in the Young (CRY), are committed to providing cardiac screening to all competitive athletes including triathletes.

There is very little known about the effects of triathlons on the heart. We hope to build a partnership with triathlon organizations, which will foster research into the field and ensure the safety of the sport for many years to come.

Many thanks to Dr. Ahmed Merghani (BMedSci, MBBS, MRCP) and Prof. Sanjay Sharma (MD, FRCP (UK), FESC) for their contributions to this article. Professor Sharma is the medical director for the Virgin London Marathon, Consultant cardiologist for the CRY sports cardiology clinic at St George’s Hospital, cardiologist for the English Institute of Sport, British Rugby League and the British Lawn Tennis Association. Professor Sanjay Sharma is Professor of Cardiology and Lead for the Inherited Cardiomyopathies and Sports Cardiology Unit at St George’s Hospital in London, England.