The first hurdle for any runner is getting out the door and completing runs on a regular basis. Once you accomplish a distance goal, your next goal will likely be to see how quickly you can run a 5K, 10K, or further. But in order to speed up, you have to start incorporating speedwork — a general term for a focused session that pushes you over your aerobic threshold (past Zone 2) — into your training. In this article, I’ll break down the four basic types of speedwork, including tempo, intervals, fartleks, and hills.

The Building Blocks of Speedwork

At its core, speedwork trains you to be able to efficiently hold the fastest pace possible at the most efficient heart rate for a given distance. To optimize your ability to run faster and improve your efficiency, you need to leverage the building blocks of speedwork, which include duration, intensity, volume, and recovery.

Changing the proportions of these four variables in your daily workouts is what can make or break your progress. Simply put, 3000 m of work can be achieved through very different experiences, whether it’s 10 x 300 m, 3 x 1000 m, or a 3000 m tempo run. How intense and how much recovery you get between repetitions will have you utilizing different energy systems. It’s also worth noting that you will do different kinds of speedwork as you progress towards your goal race.

Now let’s dive into the four basic types of speedwork, and how you can utilize each one to your advantage.

Tempo: Fast and Steady

There are many different names for a high-intensity, continuous effort, including tempo, critical velocity, steady-state, or threshold. It is generally accepted that your tempo pace is your 60-minute race pace, and a tempo run usually lasts between 20-40 minutes. The major physiological benefit of tempo runs is to help you improve your anaerobic threshold, ultimately improving your ability to maintain a moderate to high pace. Note: You may also see workouts listed as “Tempo Interval”, which are used to help extend your total time at a given pace that might be unattainable if you were to run it all at once. Don’t worry, we’ll discuss more on how to run intervals shortly.

Key Benefits

- Builds your mental confidence for running at a faster pace in races.

- Builds your ability to manage your goal pace later in a race.

- Improves your ability to manage the lactate levels you’ll have to manage on race day.

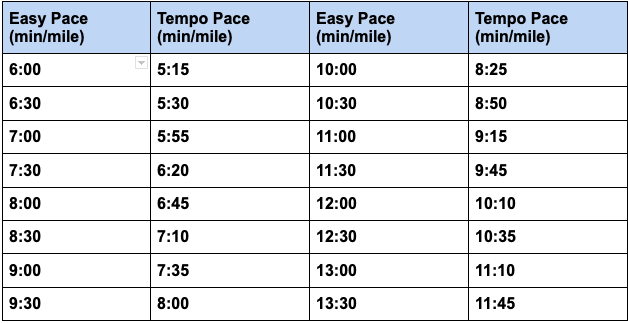

Use the chart below to understand how to define your tempo pace based on your easy pace.

Intervals: Fast and Short Repeats

Intervals have two main components — an ‘ON’ period in which you run a specified distance (or amount of time) at a specified pace followed by an ‘OFF’ period of either active or passive rest — that are repeated a certain number of times. This is where most people start to shutter, whether from bad memories of high school drills or from fear of the unknown. In the U.S., most believe that tracks are only suitable for elite runners, but it’s simply not true!

The structure and design of intervals are endlessly variable and can be used to build speed, power, and endurance. They can be structured as ‘cut downs’ (1000 m, 800 m, 600 m, 400 m), pyramids (400 m, 600 m, 800 m, 600 m, 400 m), or more traditionally (10 x 400 m).

The goal of these intervals is to run at VO2 max for a set distance or time and then recover. Your VO2 max is defined as the slowest pace at which you reach your maximum oxygen consumption. For most people, this falls somewhere between one-mile race pace and two-mile race pace. VO2 max intervals top out at about 3 minutes in duration and become threshold intervals beyond that point. Threshold intervals would commonly be workouts like 1-kilometer repeats, 1-mile repeats, and beyond, which are typically completed at 5K and 10K race paces. The longer you intend to race, the more beneficial longer intervals will be.

Early on in your training, you’ll want to maximize recovery so that you can confidently hit pace. But as training progresses, your body will adapt to need less rest so that you perform your best on race day.

Key Benefits

- Improves VO2 max and your body’s ability to utilize glucose as fuel.

- Improves running economy and efficiency because of higher turnover rate and increased level of conditioning.

- Shorter intervals allow for a greater focus on form and mechanics.

- Boosts your ability to pace yourself and understand what race day can feel like.

Fartleks: Unstructured Intervals

Fartleks are the unstructured second cousins twice removed of intervals. Fartleks are basically free-form speedwork that don’t follow a structured pattern and instead rely on the athlete to run (by feel) to the nearest mailbox, large oak tree, park bench, or top of a hill. From a coaching standpoint, I use these workouts to give my athletes a mental break from the structure of standard interval sessions, and they can especially be useful during a rest week.

Without a defined ‘ON’ and ‘OFF’ period, the only structure Fartleks have is the total workout time (e.g., 15-30 minutes). For the athlete that demands structure, I tell them to run a mix of 30-second to 3-minute intervals as they feel it. I encourage you to run these in loops, or in a park over rolling terrain to help build speed over different topographic conditions.

Key Benefits

- Provides a mental break from structured training while still supporting your aerobic fitness.

- Allows you to play with speed and practice surges that replicate a race day environment.

- Allows you to explore new areas without having to have the perfect setup of flat sections. Teaches you to adapt to variable terrain.

Hills: Form and Pacing

Hills don’t need to be something you hate. In fact, running uphill is the most beneficial type of speedwork for building your running mechanics. It’s very difficult to run uphill without driving your knees, swinging your arms, and leaning forward. Hills are also a great place to start before you hit a track because you get all the aerobic benefits while building strength in your legs, which will ensure you can handle the forces you’ll incur in speedwork. I always recommend that athletes do 3-4 weeks of hill running before jumping back on the track.

Hills are humbling because they aren’t about running fast. Rather, they force you to pace yourself early so you can stay driving into the finish. Hills aren’t all created equal, and you can learn a lot about how to leverage different kinds of hill workouts to benefit your 5K, 10K, and Marathon training goals.

Key Benefits

- Forces you to land mid-foot and imparts a great forward lean, providing an opportunity to work on your upper body mechanics.

- Phenomenal pre-speedwork builds your aerobic/anaerobic capacity. Consider hill conditioning before you hit the meat and potatoes of intervals.

- Teaches you to gauge your workout based on your perceived effort rather than a numerically defined pace.

Putting it All Together

Any good training plan should have a mix of all four types of speedwork spread out over your build-up to your goal race. Each of these workout types overlaps energy systems that need to be touched on regularly in a cycle to avoid losing your sharpness in any one direction. Unless you’re training strictly for uphill races, keeping your workouts diverse will help you avoid burnout and keep you motivated and engaged as your training builds.