This is Part Five of a five-part series on total load, the cumulative training and life stress an athlete experiences while training. Read Part One, Part Two, Part Three, and Part Four to get the full story.

No series looking at total load would be complete without an examination of the main mechanism by which the body repairs itself and recovers: sleep. While perfect sleep is quite easy to imagine (and desire!), it’s not that easy to achieve.

What are the problems with the less-than-perfect sleep that almost all of us encounter, either on a temporary or ongoing basis, and how do these affect total load?

Perfect Sleep

Perfect sleep is not defined as a certainnumber of hours each night, but rather it:

- Has 90-minute cycles comprisingperiods of light sleep, deep sleep, and REM sleep, with more deep sleep at thestart of the night, and less later on.

- Has a number of 90-minutecycles per night, usually five for most people when averaged across the week.

- Fits in with your personal bodyclock or circadian rhythm, which is reset by the daily light/dark cycle (i.e.when your body naturally wants to be asleep).

- Satisfies our sleep pressure.This is our need to sleep which has built up during the day, and which carriesover from nights of insufficient sleep.

- Has good sleep hygiene (i.e.cool, dark, quiet, comfortable).

- Includes 20- to 30-minute napsin the early or late afternoon, especially if training or competing later inthe day, or if night-time sleep quantity or quality has been reduced.

Why Do We Need Quality Sleep?

There are plenty of articles out there with advice on how to prepare for effective sleep, but why do we need good sleep? In general, sleep facilitates recovery from damage accumulated during the previous period of wakefulness, and is especially important for athletes.

Good sleep is needed to maintain the performance of thinking and problem solving, carbohydrate metabolism and the appetite associated with particular blood sugar levels, and the performance of the immune system in identifying and neutralizing invading pathogens. The first four hours of sleep are especially critical, as this period has the largest amount of deep sleep when human growth hormone (HGH) and testosterone are produced. These are the hormones responsible for the compensation response to exercise when our muscles and metabolism become stronger and more powerful.

Good sleep resets the calibration of ourinternal perceived exertion (RPE) scale, and maintains good sensations offatigue and mood. Workouts (especially high-intensity ones) feel easier when wehave slept well, so are more likely to be completed as prescribed. Extendedendurance workouts are more satisfying and our pacing strategy is also betterwhen we have slept well too.

With such clear benefits, you would expect that athletes take sleep as seriously as training, but according to surveys performed by Dr. Shona Halson at the Australian Institute of Sport, this is seldom the case, even amongst elite athletes.

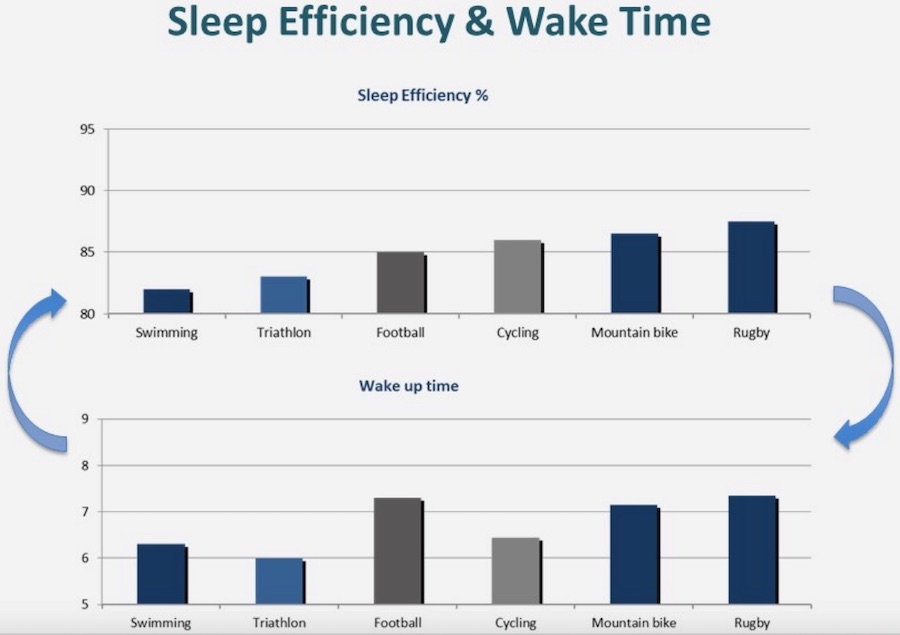

As the chart below shows, sleep efficiency(the proportion of time spent asleep whilst in bed, often used as a roughmeasure of sleep quality) and wake-up time are related, with swimmers andtriathletes having the earliest rise times, coupled with the poorest sleepefficiency:

So, although athletes need more sleep thantheir less-active peers, they often get less, resulting in daytime sleepinessas well as reduced performance.

Less-Than-Perfect Sleep

So, what typically prevents athletes fromgetting good sleep?

- Sleep hygiene: Poor bedtime routine, use of phones and TV in bed, bedding and room temperature mismatched.

- Body sensations: Fatigue, injury, muscle soreness, nervous system activity—especially from using caffeine or training late in the day.

- Travel: Jet lag, shared hotel rooms, shifts in time zone, training/competition times.

Overall, a lack of awareness of theimportance of good sleep is what prevents athletes from paying sufficientattention to the factors they can control.

How Does Sleep Interact With Other Total Load Components?

Nutrition

A chronic lack of sufficient sleep hassignificant effects on the regulation of blood sugar levels, increasingappetite for sweet sugary foods and the likelihood of contracting type 2diabetes. On the other hand, an evening meal that includes high GIcarbohydrates more than one hour before bedtime has been shown to increase theamount of REM sleep and reduce the time required to fall asleep.

Diets high in protein may improve sleepquality slightly, but high-fat diets may negatively influence total sleep time.Foods naturally high in amino acid tryptophan, such as turkey and pumpkin seeds,may improve both sleep latency and quality.

Mental Stress

In Part 3 of this series, we looked at the effects of mental stress, and how high levels of perceived stress can reduce endurance athletes’ maximum power output. A study by Canadian researchers used Heart Rate Variability (a sensitive marker of stress) to evaluate the susceptibility of a group of students to stress in the form of a demanding task. They found that the amount of reduction in HRV during a standard stress test predicted the degree of sleep disturbance the students experienced during the build-up to important exams.

Otherresearchers found that a higher daytime HRV predicted a shorter time tofall asleep and less arousals during the night, as well as a better sleepquestionnaire score.

This makes stress management and stress reduction techniques such as mindfulness, meditation, and deep breathing especially valuable at bedtime. It’s also said that a little love at bedtime doesn’t do sleep quality any harm, even the night before competition!

Conclusion

Sleep deprivation has significant effects on athletic performance, especially longer endurance sessions and high-intensity intervals. Most athletes don’t get enough sleep, and both napping and deliberately extending sleep on some days to get in the missing 90-minute cycles are very likely to have positive effects on performance, total load, and overall life satisfaction.

References

Andrews, L. (2016, November 3). International Olympic Committee’s Recommendations for Total Load in Sport. Retrieved from https://www.myithlete.com/international-olympic-committees-recommendations-total-load-sport/

Blanchfield, A.W. et al. (2018, May 31). The influence of an afternoon nap on the endurance performance of trained runners. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/17461391.2018.1477180?needAccess=true

Gouin, J.P. et al. (2015, February 7). High-frequency heart rate variability during worry predicts stress-related increases in sleep disturbances. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25819418/

Halson, S.L. (2014, May). Sleep in elite athletes and nutritional interventions to enhance sleep. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24791913/

Werner, G.G. et al. (2015, March). High cardiac vagal control is related to better subjective and objective sleep quality. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301051115000447