As this is being written, more and more stories are hitting the news about elite athletes being sidelined with the COVID-19-related complications. Among others, these include World Tour cycling athletes and a Florida Gators basketball student-athlete. It’s likely that in the coming months, we will continue to see instances of sports performance adversely affected by previous COVID-19 infections. As such, it’s essential that we as coaches inform ourselves of the long-lasting damage COVID-19 can inflict on our athletes, and create a plan to guide them through their return to sport.

How COVID-19 Infects and Where It Wrecks the Most Damage

Because of its unique entry into the body, COVID-19 is now thought of more and more as a vascular disease that spreads through respiratory pathways. That means it primarily affects not just the nose, throat and lungs but also blood vessels, kidneys, gastrointestinal tract and heart. When COVID-19 causes heart damage, it becomes particularly scary.

Myocarditis, in simple terms, is inflammation of the heart. This inflammation enlarges and weakens the heart. It can also create scar tissue which restricts the heart’s ability to pump blood and circulate oxygen. 38% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients suffer from myocarditis to some degree. Looking at athletes specifically, a recent Ohio State study found that out of the two dozen plus athletes who tested positive for COVID-19, 30% had cellular heart damage and 15% showed signs of myocarditis.

Although we have yet to see examples of this sort of data gathered from aging athletes, it should be noted that masters level athletes are the patients most frequently seen in sports cardiology clinics, which could imply they are more susceptible to myocarditis than their younger counterparts.

What Coaches Should NOT Do

Before we dive into building out a post-COVID-19 reintroduction to sport plan, I’d like to make note of the most helpful role coaches can take in this scenario. Throughout the entire COVID-19 process (starting with infection and ending with complete recovery), the coach should not attempt to insert her/ himself into the diagnosis process. Rather they should provide perspective and support as the athlete works through the unique challenges COVID-19 presents to their body.

Furthermore, the coach should not take it upon themselves to know the clinical presentation or pathophysiology of myocarditis. However, they should understand cardiovascular signs and symptoms of myocarditis or other cardiac conditions and how they show up in exercise data and perceived exertion. In short, the coach should know when the athlete should cease exercise and should be referred to a physician for testing and diagnosis.

Return to Sport Process and Protocol

1. Coaches should understand the relative risk and reward for the athlete’s training and performance trajectory with respect to their COVID-19 diagnosis.

First and foremost, as coaches, it’s our job to provide perspective to the athlete. Many of the same personality traits that enabled the athlete to achieve success in the field are the same ones that can betray the athlete and lead them to push too hard too fast. It is imperative that we keep them focused on the long game. Sitting out a few extra days on the front-end can ultimately enable many more training days in the mid-term and long-term future.

Also, explaining to the athlete that fitness is easy to rebuild when the heart is strong and undamaged goes a long way toward encouraging training plan compliance. Consistent and effective communication is key for this stage, especially as the athlete will have many questions when deciding what training or resting to execute on any particular day.

2. Know the signs and symptoms of myocarditis during training.

Athlete feedback is of utmost importance in this step. Using the TrainingPeaks Notes Feature, it’s easy to insert the following questionnaire for each day. I’d suggest doing this for 10 days or more until the athlete is asymptomatic.

Since enduring a confirmed or suspected COVID-19 infection, have you experienced any of the following:

- Fainting or sudden loss of consciousness

- Chest pain, chest pressure, sharp pain in the heart or lungs when breathing or lying down

- Shortness of breath at rest or with exertion

- Increase in resting heart rate by >20bpm

- Palpitations (heart racing, heart skipping, or dropping beats)

- Marked reduction in fitness

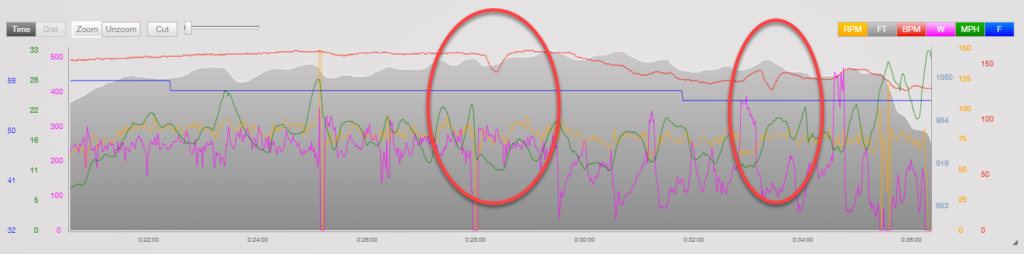

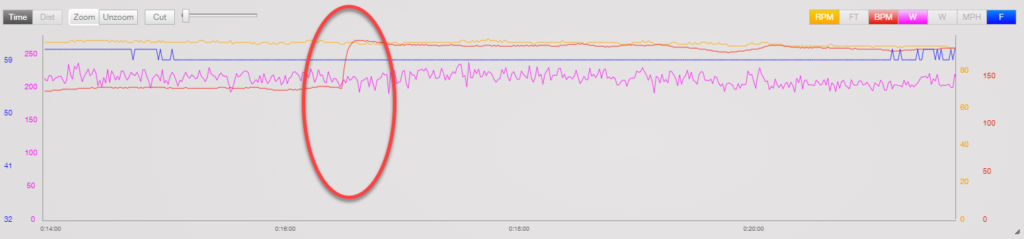

Apart from using a daily questionnaire, coaches should put in due diligence and monitor training data. For example, in order to provide a bit more clarity around alarming heart rate files, here are a couple of screenshots as examples. A coach should keep an eye out for a heart rate that seems out of the ordinary. These are not diagnostic but can be an indicator of underlying problems.

Here is an example of heart rate drop and resumption inconsistent with expectations given the athlete’s current workload.

Here is another example depicting a sudden rise in heart rate as cadence and workload stayed consistent. This athlete ceased exercise and the elevated heart rate resolved shortly thereafter.

3. Know when to limit the athlete from training or competition and when to refer an athlete directly to a physician for testing and diagnosis.

Should the athlete answer affirmatively to any of the questions in the short questionnaire or if you see any irregular heart rate data, refer the athlete immediately to a physician. The physician should decide with the athlete the best actions regarding diagnostic testing, evaluation, treatment and return to activity.

General guidelines for withholding the athlete from exercise and/ or training following a COVID-19 diagnosis should be as follows. If the athlete is…

Asymptomatic: 10 days without exercise. There is a lack of any identifiable symptoms.

Experiencing Mild Illness: 10 days of no exercise, after which they must be well in order to restart any sport. Not better, but well. Mild illness is defined as: loss of smell and/ or taste (anosmia, ageusia), headache, mild fatigue, mild upper respiratory tract illness and mild gastrointestinal illness.

Experiencing Moderate Illness: They must complete isolation until they are fever free for 24 hours. The athlete can then start a period of no exercise lasting 10 days. Moderate illness is defined by: persistent fever, chills, muscle soreness, lethargy, dyspnea, and chest tightness.

Experiencing Severe Illness: This is generally defined as being hospitalized. The physician team will include cardiac imaging as part of treatment and then proceed as they deem appropriate.

4. Understand how to slowly and safely return an athlete to sport.

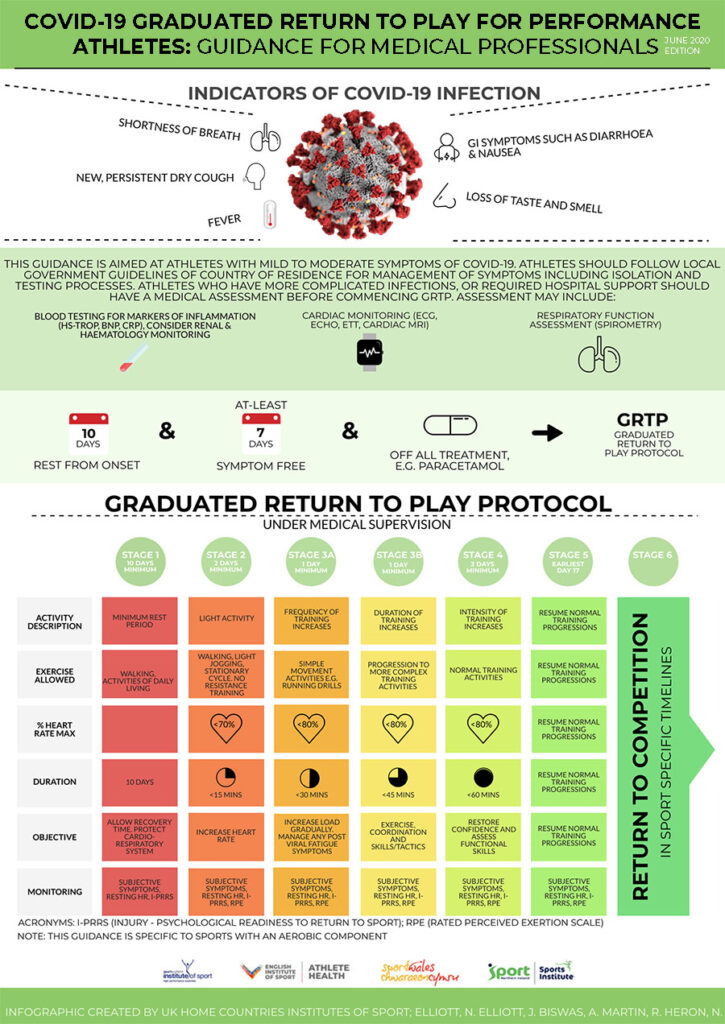

The infographic below does a great job of providing guidelines on how to do so.

Source: The Faculty of Sport and Exercise Medicine

Additionally, if an athlete is diagnosed with myocarditis, the American College of Cardiology recommends the following before the athlete is cleared to return to sport: Athletes diagnosed with myocarditis should be restricted from exercise for three to six months to promote resolution of inflammation, depending on the clinical severity and duration of the illness, LV function, and extent of inflammation on cardiac MRI.

Athletes with a history of myocarditis have an increased risk of recurrence and, therefore, should undergo periodic reassessment, especially within the first two years. It is reasonable for athletes to resume training and competition if all of the following criteria are met: LV systolic function has returned to the normal range, serum biomarkers of myocardial injury have normalized, and clinically relevant arrhythmias are absent on ECG monitoring and exercise stress testing.

5. It is imperative that throughout the COVID-19 recovery process, the athlete’s mental health is monitored by the coach.

Additionally, their coach should know when to reach out to a professional for a consultation. A COVID-19 diagnosis alone could be disruptive or even catastrophic to the athlete’s emotional well-being. Psychological follow-up, and in some cases intervention, are recommended to help athletes emotionally as they return to sport.

To conclude, this article is written close to Jan. 1, 2021, and is based on research articles authored in early Nov. 2020. Our understanding of COVID-19 continues to evolve, so stay vigilant in pursuing scientific updates. This article can help prevent life-threatening situations for an athlete, but it is not a substitute for an emergency action plan that ensures quick response by paramedics and defibrillation.

Thanks for reading. Stay safe.