How does a world-class marathoner adapt her training for the grueling demands of a trail 100K? In this technical breakdown, CTS Ultrarunning coach Cliff Pittman answers a series of questions to pull back the curtain on Molly Seidel’s preparation for the 2026 Black Canyon 100K.

Focusing on the critical concept of “durability” — or fatigue resistance — Pittman explains why maintaining performance late in a race is more important than a high physiological ceiling in ultra-distance events. Learn the specific methodology behind her build, from the shift toward cumulative mechanical load and mini-blocks to the importance of high-volume Zone 2 aerobic running.

What is durability or muscular endurance, and why does it matter for performance in ultras?

Durability, often referred to as fatigue resistance, describes an athlete’s ability to maintain a high fraction of their aerobic capacity and movement economy as fatigue accumulates over long durations. In practical terms, it is the ability to keep producing the same output at a similar physiological cost late in a race, despite the cumulative effects of musculoskeletal loading, glycogen depletion risk, thermal strain, and neuromuscular fatigue.

In shorter events such as the 5K through the marathon, performance is largely determined by VO2max, lactate threshold (or critical speed), and running economy. These qualities still matter in ultradistance racing because they define the athlete’s physiological ceiling. However, as race duration increases, other determinants begin to dominate. In ultras, the outcome is often dictated not by how high that ceiling is, but by how much of it the athlete can still access after several hours of running.

For Molly, the goal is not to build aerobic fitness by traditional definitions such as VO2max or Lactate threshold. She already possesses world-class aerobic development. The objective is to ensure that this fitness remains usable deep into a 100K race. Durability is what allows that to happen. It helps preserve running economy, limit pace fade, and maintain stable fueling and hydration so the aerobic system can continue to function effectively from start to finish.

What are the key workouts and approaches you and Molly are using to improve durability going into Black Canyon, and how does this fit into a broader block-periodization approach?

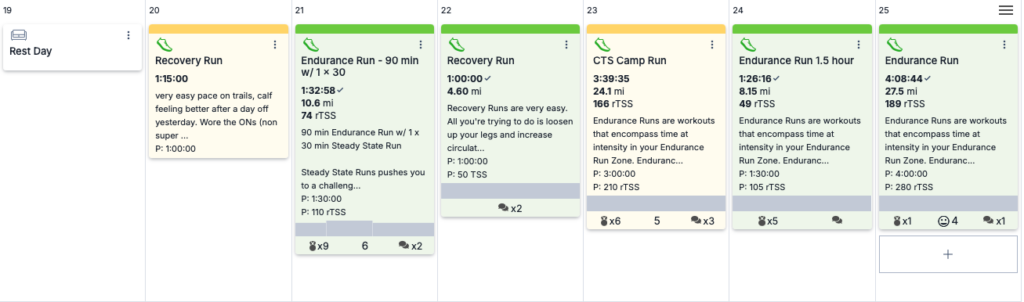

Molly’s preparation for Black Canyon has been intentionally straightforward and, on paper, arguably boring. The foundation of the block is a high volume of Zone 2 aerobic running, supplemented with controlled doses of Zone 3 work that are layered into long runs at race-relevant effort. The emphasis has been on time on feet, consistency, and specificity rather than frequent high-intensity sessions. This is very specific to her and her training history.

Coming off a threshold-focused block leading into the NYC Marathon, the transition into ultra preparation involved increasing overall volume while reducing intensity. This allowed us to shift the primary training stress from metabolic intensity to cumulative mechanical load. With intensity kept relatively contained, we could increase training density by stacking back-to-back long runs or several medium-long runs in succession. This creates meaningful fatigue while still allowing for adequate recovery.

The higher the intensity of training, the more polarized the week must be, with very clear separation between hard efforts and recovery. In this phase, by keeping most of the work aerobic, the “math” of the week changes. We can accumulate fatigue over multiple days, which is critical for developing durability, without compromising recovery or increasing injury risk. This block-oriented approach allows us to maintain Molly’s existing aerobic capacity while building the fatigue resistance required to express that fitness over 100 kilometers.

How are you using mini-blocks to structure training, why does this approach work, and how can athletes apply it themselves?

Traditional training terminology often describes microcycles as 7-10 day units that sit within mesocycles of several weeks. The mini-blocks we use with Molly are smaller stress clusters nested inside those microcycles. Over a 7-10 day window, training is organized into short sequences of two to three higher-volume or key aerobic sessions, followed by one to two days of reduced volume or recovery running.

This structure works particularly well for ultra development because it better reflects the cumulative fatigue experienced in racing. Instead of isolating a single long run surrounded by fresh days, the athlete learns to run efficiently, fuel appropriately, and manage effort while carrying residual fatigue. This repeated exposure is a key driver of durability.

For other athletes, the principle is transferable. The intensity of these mini-blocks must be low enough that sessions can be repeated on consecutive days. One session should act as the anchor workout, such as a long run or extended steady effort, while the surrounding days add volume rather than intensity. Importantly, these blocks must be followed by genuine recovery to allow adaptations to occur. The goal is not to survive the block, but to absorb it.

How have you worked with Molly to improve other aspects of trail and ultra performance, such as fueling, hydration, and technical ability, and why do these matter as athletes move up in distance?

As athletes transition from the marathon to ultras, execution becomes an increasingly important determinant of performance. Limitations are often no longer purely physiological but practical, including fueling tolerance, hydration strategy, pacing discipline, and the ability to manage variable terrain efficiently.

With Molly, we have leaned heavily into specificity. She has spent a good amount of time on the Black Canyon course and similar terrain to build familiarity with the technical demands and pacing rhythm required. Downhill running, in particular, has been treated as a skill rather than an opportunity to push intensity, with an emphasis on relaxed mechanics and controlled effort.

Fueling and hydration have required a substantial learning curve. Compared to marathoning, ultra fueling demands higher intake rates over longer durations, with greater consequences for small errors. Following GI issues at Bandera that were likely related to sodium and hydration imbalances, we brought in Stephanie Howe, PhD, to help us further dial in Molly’s strategy. The goal has been to develop a simple, repeatable plan that supports fluid absorption, minimizes GI distress, and allows consistent energy delivery rather than reactive intake late in the race.

These factors matter because, in ultras, small execution issues compound over time. A stable fueling and hydration strategy helps preserve durability by preventing cascading fatigue, GI shutdown, or pacing collapse in the later stages of the race.

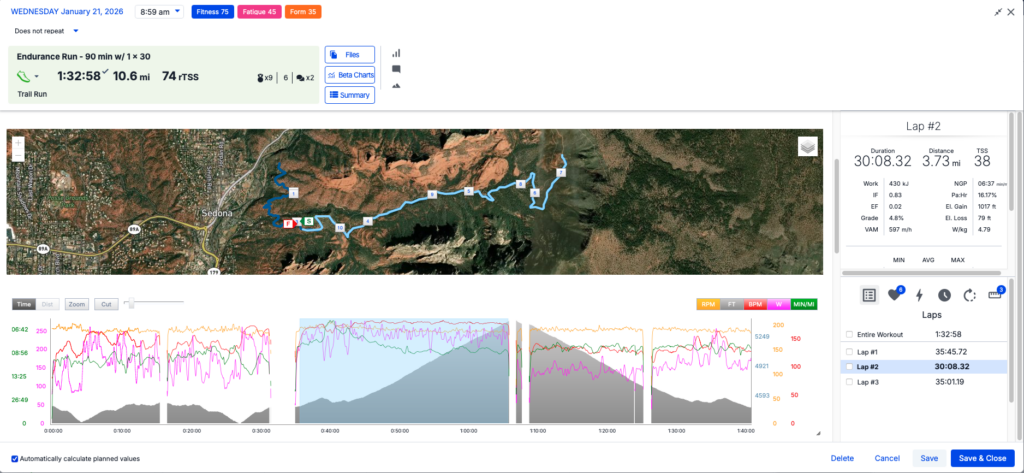

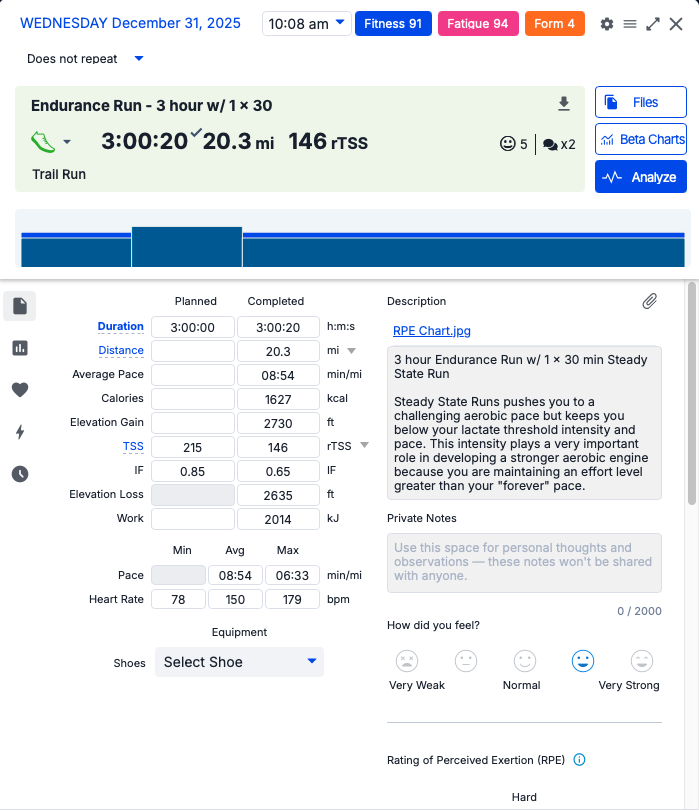

How have you used TrainingPeaks metrics to help plan and analyze Molly’s training?

Most of Molly’s training is prescribed by perceived effort and terrain context, which is essential for trail running where pace alone can be misleading. TrainingPeaks metrics are then used on the back end to evaluate how the work was executed and how her body responded.

We rely heavily on Normalized Graded Pace to account for elevation changes and allow for more meaningful comparisons across routes. Intensity Factor provides a high-level check on how demanding sessions are relative to her current functional threshold, particularly during long steady segments. We also closely monitor Pa:HR to assess cardiac drift, which offers insight into durability, heat stress, and fueling or hydration issues.

Rather than chasing individual numbers, we look for patterns. Over time, improved durability shows up as the ability to complete more work at the same perceived effort with less physiological drift and better late-run stability. These metrics help guide decisions around recovery, training density, and whether the plan is producing the intended adaptations without accumulating excessive fatigue.