The abbreviation ‘VAM’ originates from the Italian term velocità ascensionale media, which translates indirectly to average ascent speed. The term is relatively self-explanatory. It measures the rate of climbing, specifically how many vertical meters you are climbing per hour. The value is calculated as (meters ascended × 60) / minutes ascending. Most modern GPS devices can calculate this and give you a live VAM reading as you ride. TrainingPeaks also calculates VAM for a section of a workout as long as speed and GPS data is present.

VAM originates back to the 90s when the metric was created by the Italian physician and cycling coach Dr. Michele Ferrari. He later became known for supplying performance-enhancing drugs to some of cycling’s most prominent names. Originally, VAM was used to measure pure climbing performance, helping provide power-to-weight ratio estimations before power meters became commonplace. It can give insight into the performance of professionals where most data is protected from view.

How is VAM used today?

VAM still has strong relevance today because it is a valuable metric for making simple objective comparisons between climbing performances across the World Tour and all levels of racing. VAM has little to no use on flat terrain or short and shallow climbs. However, cyclists may use it to pace themselves on a long alpine climb, for example, where they do not have access to a power meter. In this scenario, VAM can be a handy measure of performance and in helping you to pace your effort, especially when an average one-minute value for VAM is displayed.

Unlike power, VAM can be affected by factors such as headwinds and heat — though the impact of headwinds is reduced in sheltered, steep climbs. Road surface and bike choice will also impact the VAM that a cyclist can achieve. Despite these factors affecting VAM, perhaps the most critical principle surrounding it is how the gradient has an exponential effect on the metric. In short, the steeper the incline, the easier it is to obtain a higher VAM due to factors including rolling resistance and air resistance having less effect at the lower speeds. Ignoring air resistance and friction, the power required to sustain VAM values across gradients is the same.

What is a good VAM number?

So, now we know what and how VAM is used, what are typical rates a coach could expect to see? In World Tour races, you might see the peloton climbing at a rate of 1300-1400 m/h for an average pace. Likely, a rate that would not be sustainable for more than a few minutes for the average club cyclist or triathlete. At the top end of the pro spectrum, riders may climb at a rate of 1600-1800 m/h for long durations, especially in critical climbs.

Athletes should learn to be familiar with the VAM numbers they see on their local climbs or virtual cycling platforms such as Zwift. In the case of a power meter dropout during a hilly race, VAM can be the perfect tool to help your athletes pace themself on climbs — where blowups are most common.

How are VAM and power related?

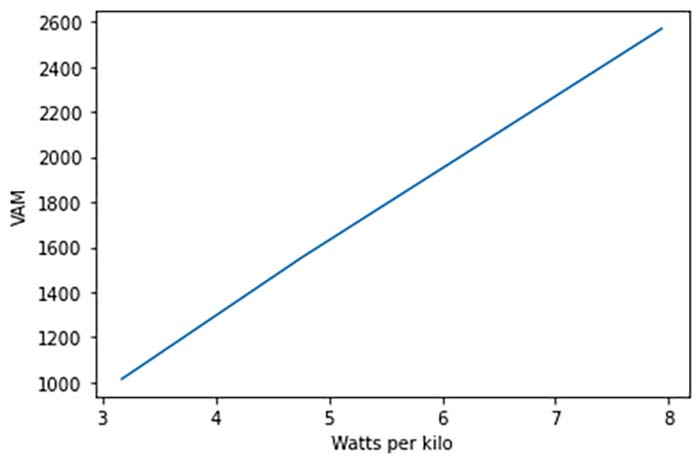

The amount of VAM achieved during a climb is linearly related to the amount of power the rider produces, divided by their weight. Let’s assume a cyclist and equipment system of 70 kilograms (154 lbs) is riding up a gradient of 8%. Ignoring complicating factors, like air and rolling resistance, we can calculate a ballpark estimate for the kind of VAM values this rider might achieve for a given power output.

The climbing speed increases with power, as you might expect. The VAM numbers on this plot would need to be generally shifted down to allow for external factors that slow you down, such as wind or rolling resistance. Climbing speed can improve by increasing power or a weight reduction — as seen on the horizontal axis.

VAM and the weather.

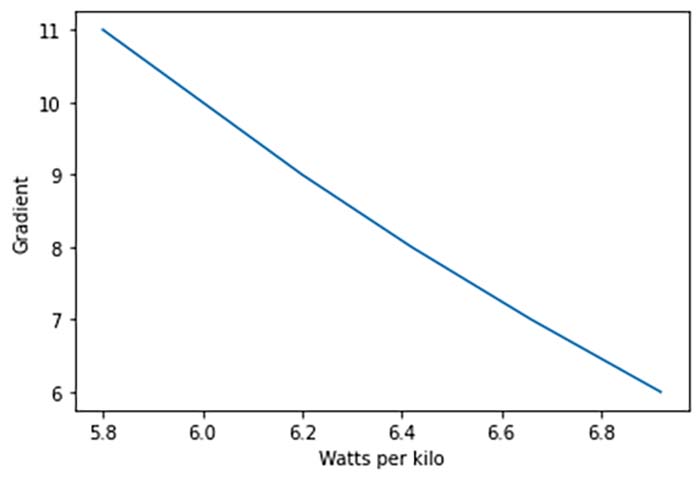

To visualize influences on VAM, let’s look at the power-to-weight ratio required to ride at a VAM of 1800 m/hour. This is a typical rate of ascension seen at the end of a Grand Tour mountain stage. The resulting graph shows the power requirements decrease exponentially to ride at a VAM on steeper gradients.

This reduced demand is due to air resistance, though rain, wind and other environmental conditions will impact the VAM a rider can achieve. Meaning that riding at a higher VAM is, in theory, easier the steeper the gradient. The gradient causes a rider to slow down as the road becomes steeper. As we ride slower — less energy goes into overcoming air resistance. This means more energy goes into overcoming gravity; thus, we can achieve higher VAM for the same power. Any context must be noted when using VAM to assess performance because these external factors can skew conclusions about the rider’s performance.

How a coach can use VAM

VAM has two purposes for a coach. The first is assessing climbing performance, and the other is helping an athlete pace a climb in the absence of other methods.

- Assessing climbing performance

VAM is used by several media outlets and sports scientists to assess how an athlete’s climb has compared to previous performances or performances of their competitors. It’s occasionally used to evaluate the legitimacy of performances in the cycling world — though unfair accusations have been leveled in the event of tailwinds. Suppose your athlete has a test climb used for efforts and performance assessments; looking at how their VAM changes across the season can be helpful. As many athletes don’t weigh themselves regularly, in place of weight data, VAM can also be used to estimate watts per kilo when no accurate weight data is available. The easiest way for a coach to analyze an athlete’s VAM is through the Training Peaks platform, which is available in the ride analytics section when you click ‘analyze’ on a ride.

- Pacing without power or heart rate

When your tech sometimes doesn’t want to work — we’ve all had a power meter die mid-ride at some point — or if an athlete doesn’t have a power meter on their bike, being familiar with VAM can help measure a climbing effort. If your athlete is racing a triathlon, a hilly road race or a time trial, going too deep on a climb can be costly. Without power, many athletes struggle to pace themselves on feeling alone, and climbs are where implosions happen. The key to using VAM as a pacing tool is familiarity with what kind of numbers go with what type of effort and knowing the technical specifications of VAM, as explained earlier in this article. Similarly, to power, just knowing the number isn’t enough – context is everything. Athletes might want to consider having a climbing field on their bike computer where climbing metrics can be displayed during their workout or race. Having ‘one-minute VAM’ as one of these metrics can be helpful in the event a power meter or heart rate monitor drops out. This field can be found on many bike computers as standard and, if not, can be added with your computer’s companion app under ‘data fields.’

The key to pacing with VAM is familiarity. Having ridden on long climbs in the past with power, your athlete will know (roughly, as it’s an estimate) what kind of VAM numbers they can achieve for what kind of effort. This is something I have done personally. In April, I rode a long climb for 53 minutes at a VAM of 1107m/hr. This climb was ridden at tempo, so it wasn’t a full-gas effort. Now I know that if I face any issues with my power meter while racing, I’ll be able to pace climbs — for example, if I ride the first few km at 1400m/hr, I know that I’m likely over-pacing, even without access to my power or heart rate data.

Conclusion

Again, VAM (velocità ascensionale media) measures the number of vertical meters gained per hour. It can be a valuable tool for coaches to assess climbing performance — especially in the absence of other data. VAM can also add important context, even with access to all of an athlete’s data. An athlete can use VAM in the event of a technological failure of whatever device they usually use to aid in measuring their effort. It’s a metric that some might consider to be outdated but should be in every coach’s data analysis arsenal.